It’s no hyperbole to argue that the UK water sector privatisation could be described as the Great British PPP Robbery. It may well become the canonical example of the problems with the privatisation of regulated utilities.

Consider the latest balance sheet of the water sector in UK.

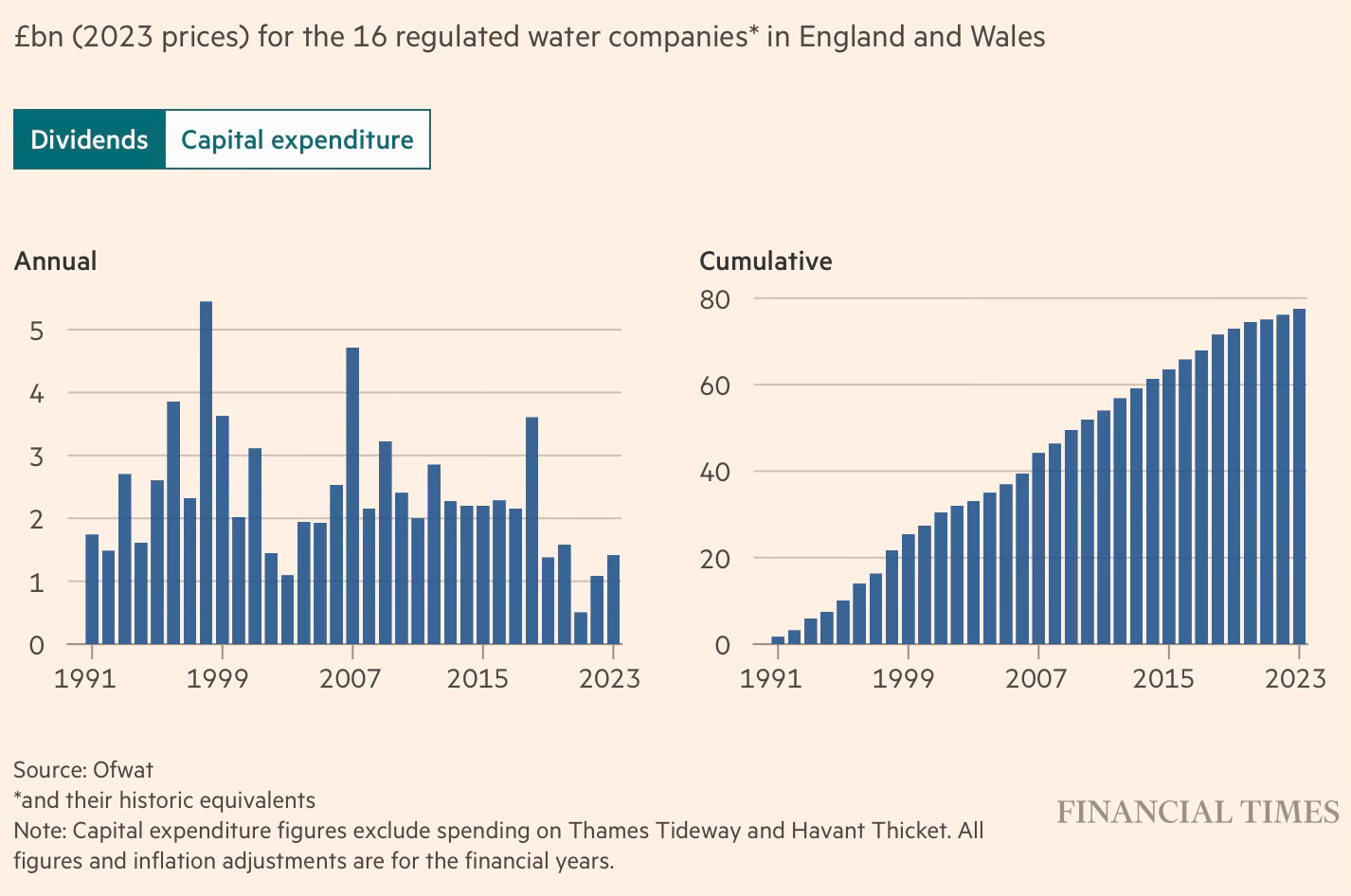

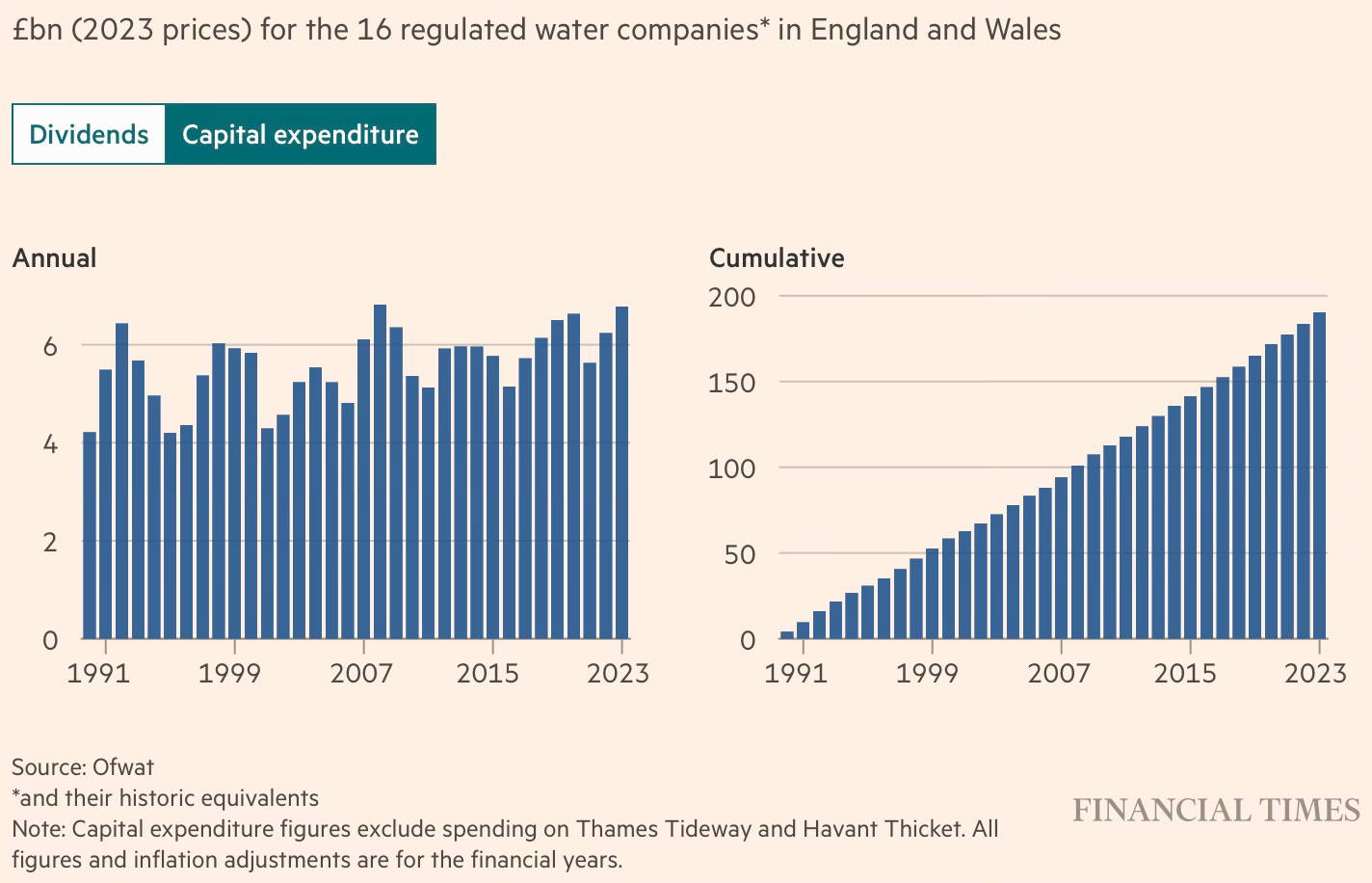

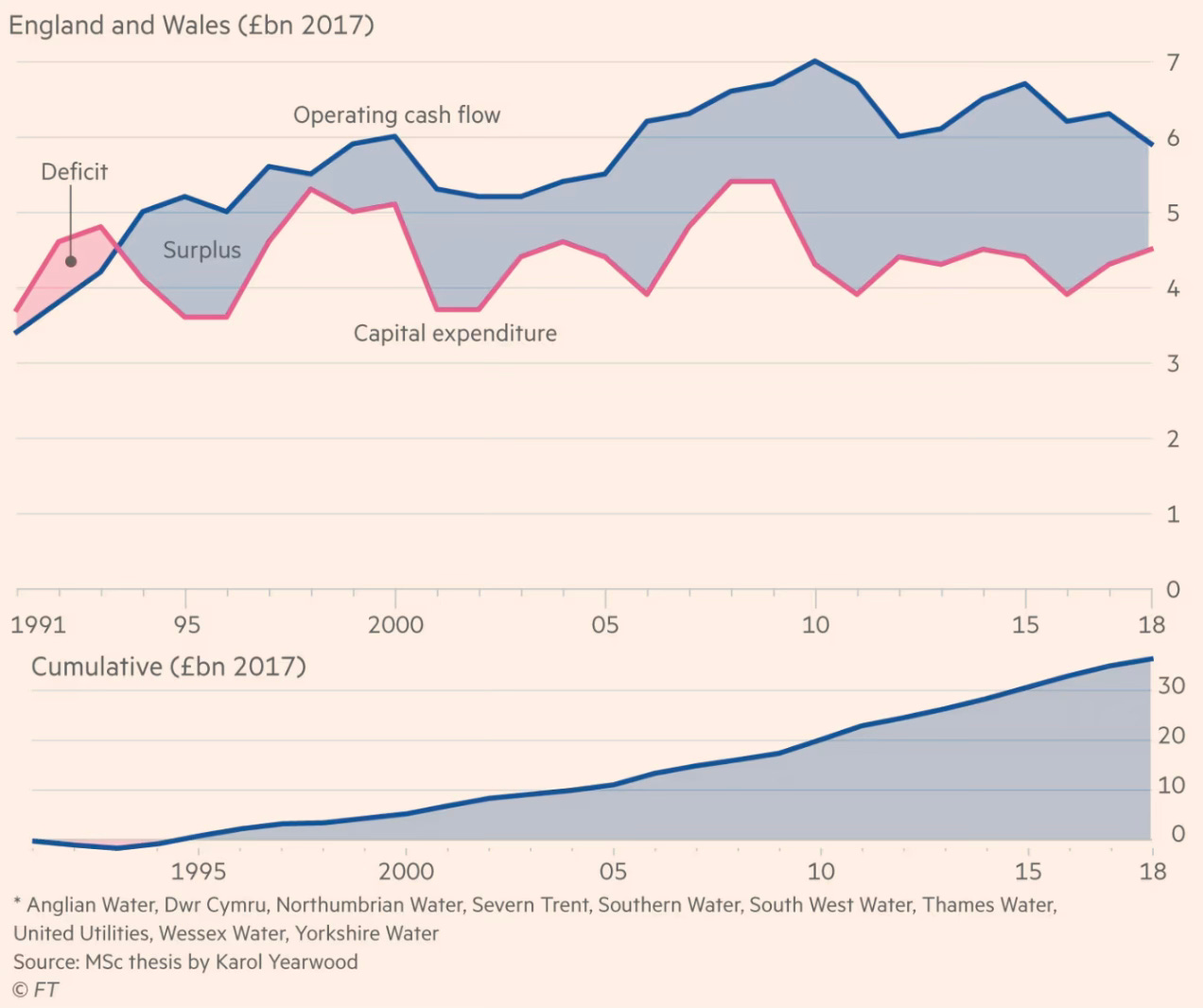

Water companies in England and Wales paid £2.5bn in dividends and added £8.2bn to their net debt in the two financial years since 2021, according to research by the Financial Times. The updated figures mean that the 16 water monopolies have paid out a total of £78bn in dividends in the 32 years between privatisation in 1991 to March 2023, according to the research, which is based on regulatory data and then adjusted for inflation. The £78bn payout is nearly half the £190bn the companies spent in the same three decades on infrastructure. The utilities meanwhile chalked up more than £64bn net in debt over the same period, despite being sold at privatisation with no borrowings.

Consider the dividend payouts since 1991.

And the capital expenditures.

In other words, in the 32 years since privatisation, the owners of the UK water companies took out or created obligations to the tune of £142 bn while investing only £190bn, or a net asset increase of just £48 bn.

The loading up of debt is a problem in regulated industries like water since the regulator takes the debt service costs into account while fixing tariffs, thereby passing the debt service costs to the consumers through their bills.

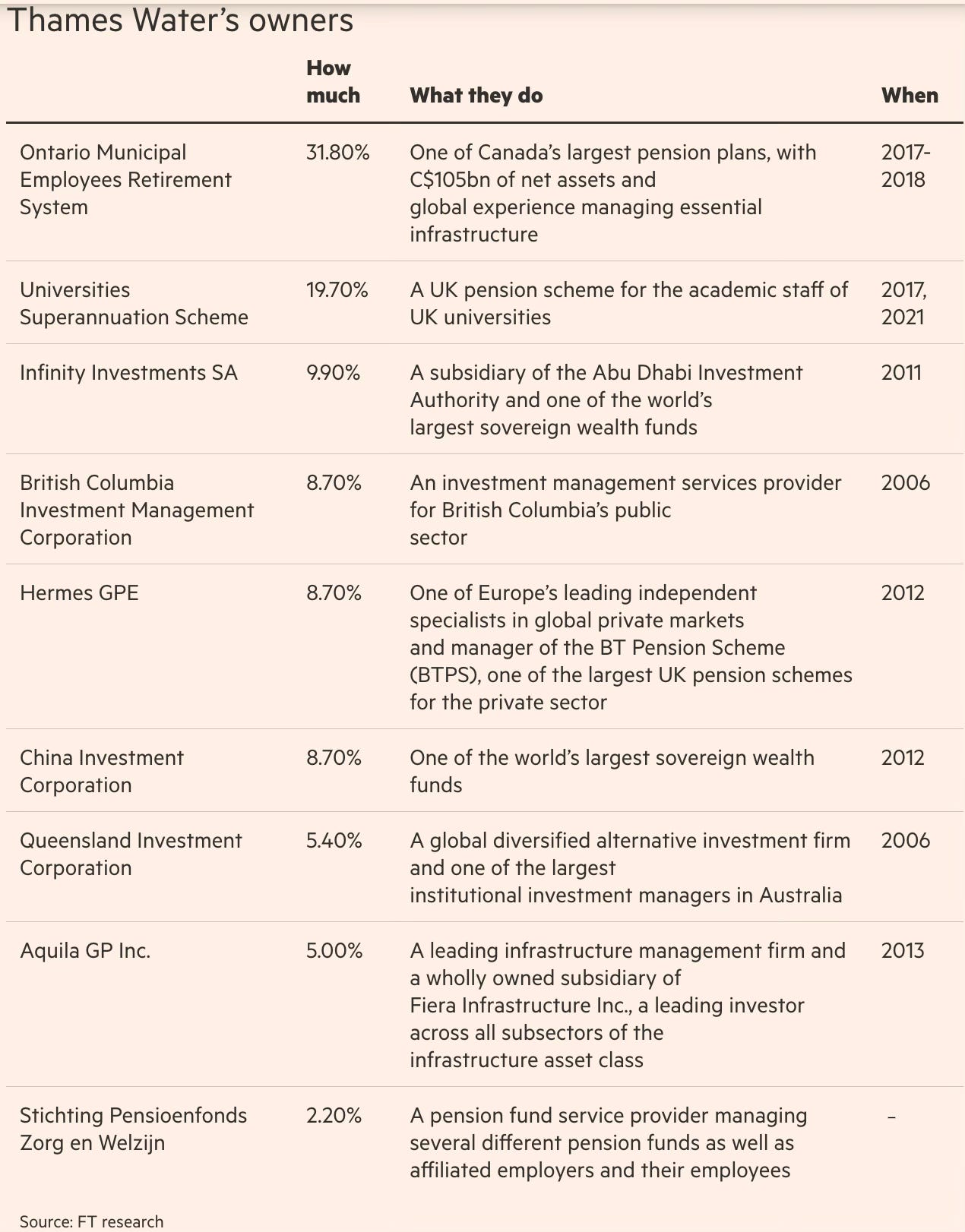

The high noon of such leveraging was the decade-long ownership of Thames Water since 2006 by Macquarie, the Australian infrastructure private equity group. A study by Karol Yearwood at Greenwich University has this summary of the financials of the company during the decade.

Macquarie borrowed more than £2.8bn to finance purchase, and later supposedly repaid £2bn of the debt through new loans raised by Thames Water through a subsidiary in Cayman Islands, effectively transferring the purchase costs to customers. Furthermore, in those 10 years, debt increased 2.3x times (from £4bn to £10bn), dividends averaged 270m per year, yet between 2011 and 2015 they paid no tax.

It’s a testament to the distortions in the market that Macquarie’s rent extraction from Thames Water has been an important motivating force behind the private equity industry’s push to invest in infrastructure.

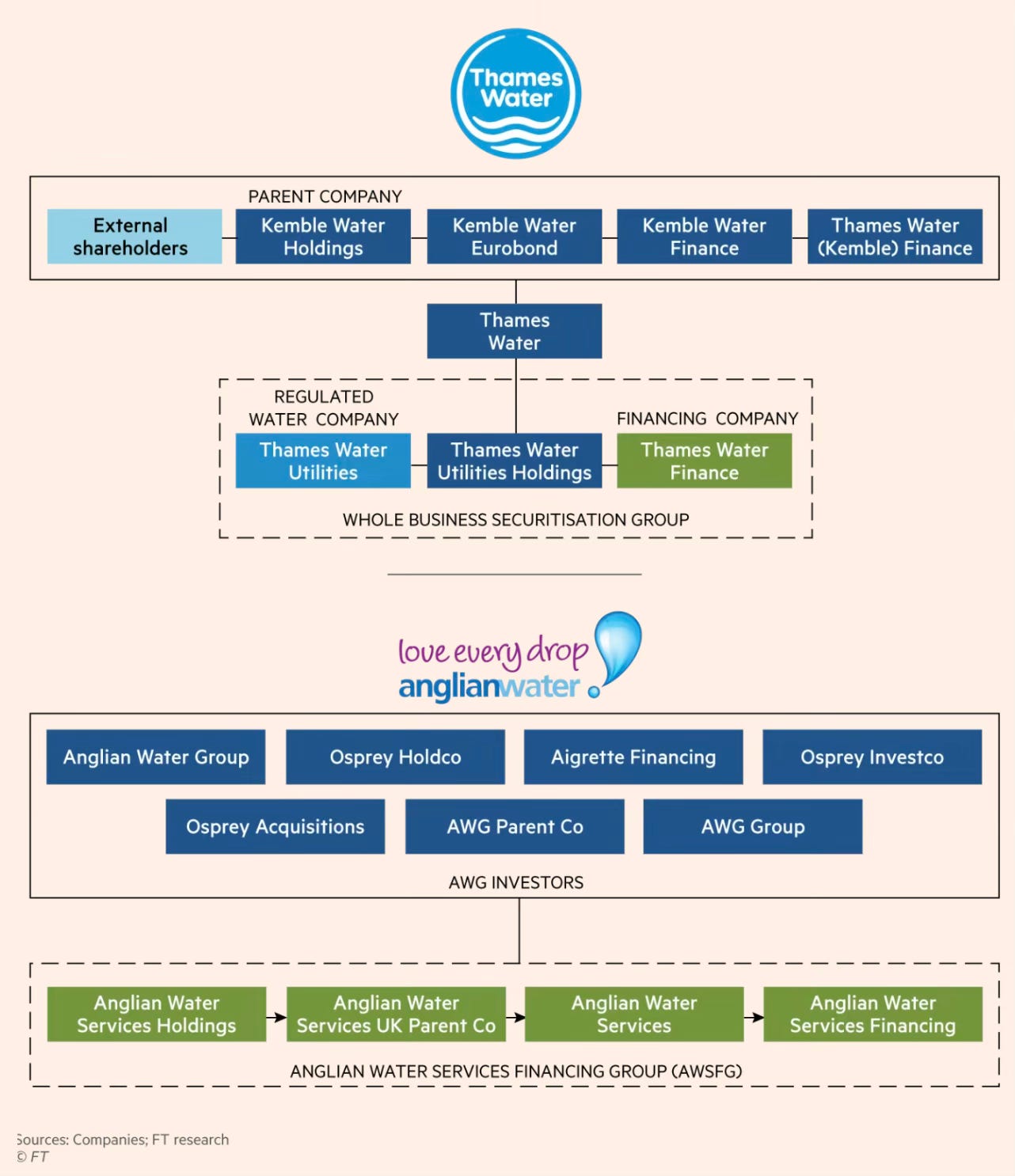

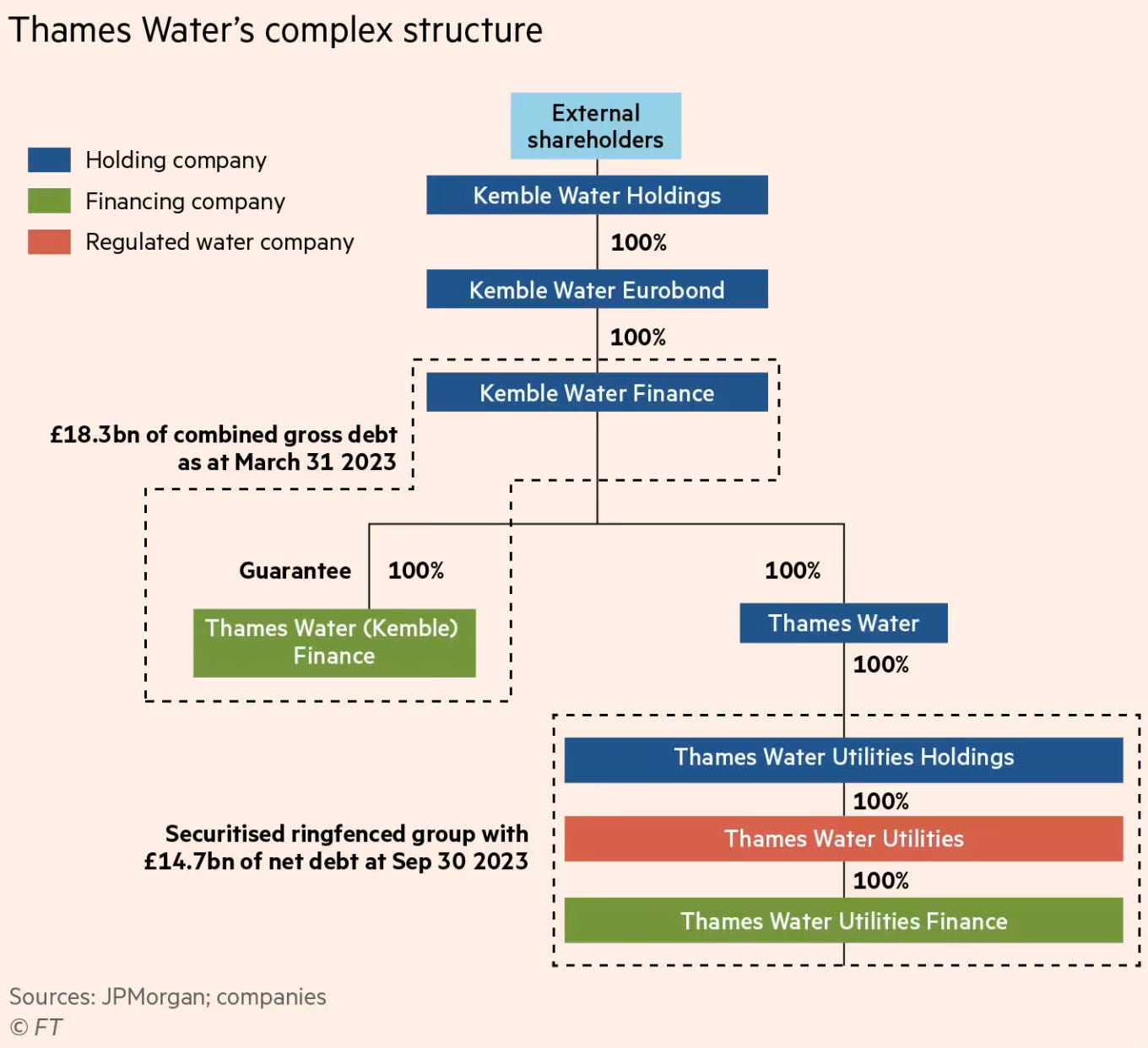

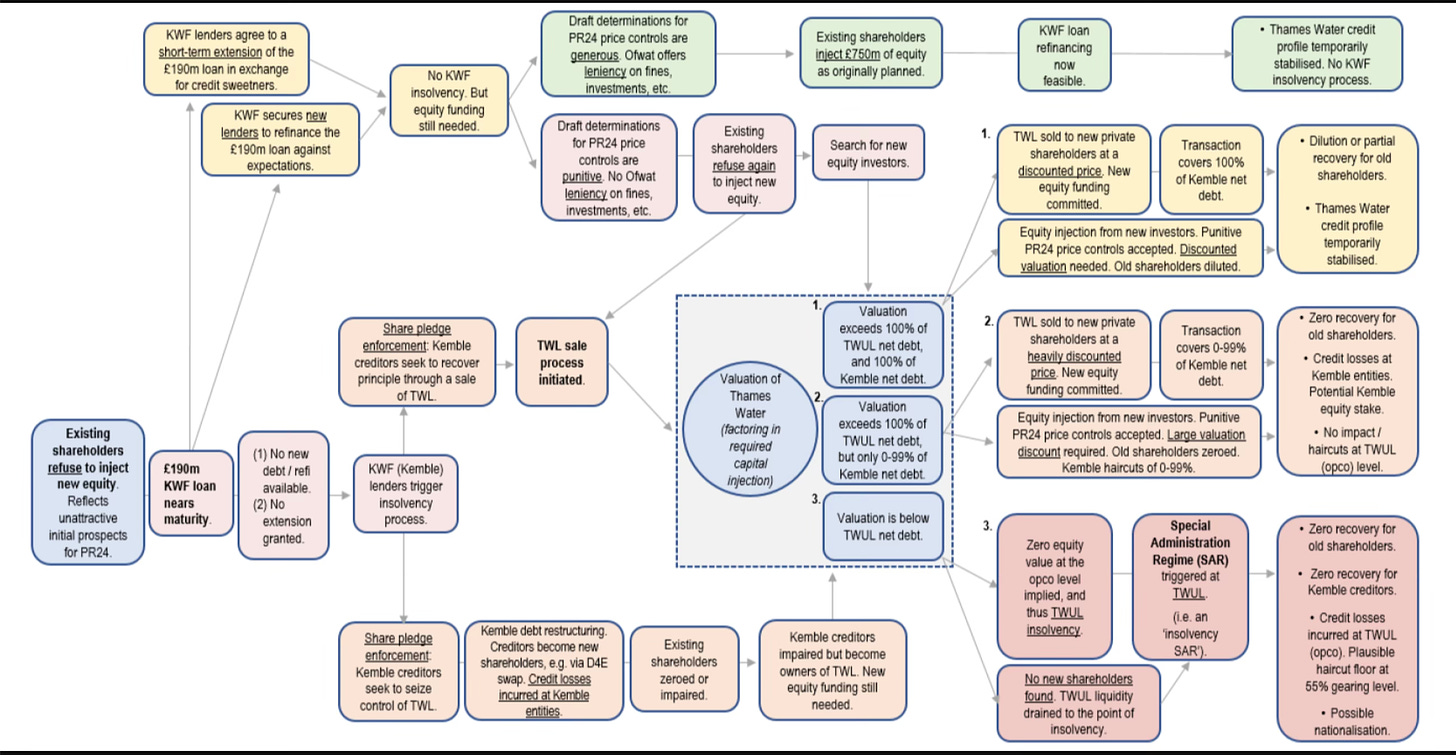

The business model of the private owners has sought to retain earnings and avoid equity infusions and instead use debt to finance investments for maintenance and upgrades while paying out dividends from cashflows. In fact, Thames Water received no equity infusion since privatisation till it got a £515mn loan at an 8% interest rate in 2023 through a convoluted structure - the loan was accounted as a debt in the books of the regulated utility’s parent company (Kemble Water), but accounted as equity in the regulated utility itself.

Thames Water, which supplies water to about 25 per cent of the population in England, presented the loan in March as “£500mn of new equity funding from its shareholders” to improve “leakage and river health” and deliver a turnaround plan. However, the recapitalisation involved the owners — which include sovereign wealth, private equity and pension funds — providing a £515mn convertible loan to Thames Water’s parent entity, Kemble Water, according to the company’s accounts. Kemble then “cascaded” £500mn of this borrowed money down the chain of holding companies that own Thames Water into the regulated utility. The £515mn increase in debt at Kemble has pushed the group’s consolidated borrowings to over £18bn, having risen from just over £15bn as of March 31 2022. The loan could convert to equity in the future. It is treated as a liability in Kemble’s accounts.

The owners have used complicated financial structures to not only load up on debt but also payout large dividends.

Britain’s privatised water and sewage companies paid £1.4bn in dividends in 2022, up from £540mn the previous year, despite rising household bills and a wave of public criticism over sewage outflows. The figures… are higher than headline dividends in the year to end March 2022. This is because several have layered corporate structures with numerous subsidiaries, only one of which — the operating company — is regulated by Ofwat… The complex arrangements enable providers to distinguish between internal dividends — payments between intermediate holding companies in the group — and external dividends to private equity, sovereign wealth and pension funds, which own the entire water and sewage business including the holding companies… water monopolies argue internal dividends are used to service debt and other costs… Thames Water, the largest water monopoly, paid £37mn of “internal dividends” to its parent company in the year to March 31 2022. This was an increase from £33mn in the previous 12 months, despite announcing that “external shareholders” had not received dividends for five years…

Adding to the complexity, internal dividends are often only included in notes to the accounts, while dividends can also be deferred until after financial results are released, enabling companies to show zero dividends for the current year in their published annual reports and accounts. Dividend payments are also often described as “cash neutral” as the funds are immediately returned to the company from within the group in payment of debts. In one example, Northumbrian Water, majority owned by CK Infrastructure Holdings, declared £272.6mn in dividends in the year ended March 2022, including an interim dividend of £58.2mn, and a final dividend of £55.4mn. The final dividend was approved after the balance sheet date and will only show as a paid dividend in the 2023 financial statements. The £272.6mn included £159mn as a special dividend, which the company said enabled a group company to pay off a loan, stating that the transaction was “cash neutral” [implying no cash leaves the business], according to the accounts.

Thames Water is not the only company facing acute stress.

South East Water, SES Water and Southern Water are all under close watch by regulator Ofwat over their financial stability. Southern Water was rescued from the brink of bankruptcy in an Ofwat-brokered deal with the Australian infrastructure manager Macquarie in 2021 but the utility was forced to suspend external dividends until at least 2025 following a credit rating downgrade last year. Investor jitters come as Ofwat is pushing them to inject more cash into the utilities. It is not clear whether investors — which include sovereign wealth funds, private equity firms and pension funds — will play ball. Few equity injections have been made since privatisation.

The business models of the companies that relies excessively on debt has taken the sector to the brink of collapse.

Ofwat wants to lower utilities’ debt. It is pushing them to reduce gearing — a measure of debt to assets — from a sector average of around 68 per cent to 55 per cent by April 2025. Peter Hope, head of regulatory finance at Oxera Consulting, said water companies will need to change how they run their finances in the next few years, given the step change in investment that is expected. “In broad terms, the industry will have to go from a situation of not having retained any earnings since privatisation, to having to retain for the next 25 years almost all of the earnings.” In addition they will have to inject £5bn equity by 2030, and £8bn in the five-year period following, according to his calculations based on the 55 per cent gearing ratio assumed in Ofwat’s modelling. “Even this does not take into account the need for future increases to replace aged assets and deal with resilience and climate change,” he added.

The problems in water supply are mirrored on the sewerage and wastewater treatment side. Consider this about investments in wasterwater treatment

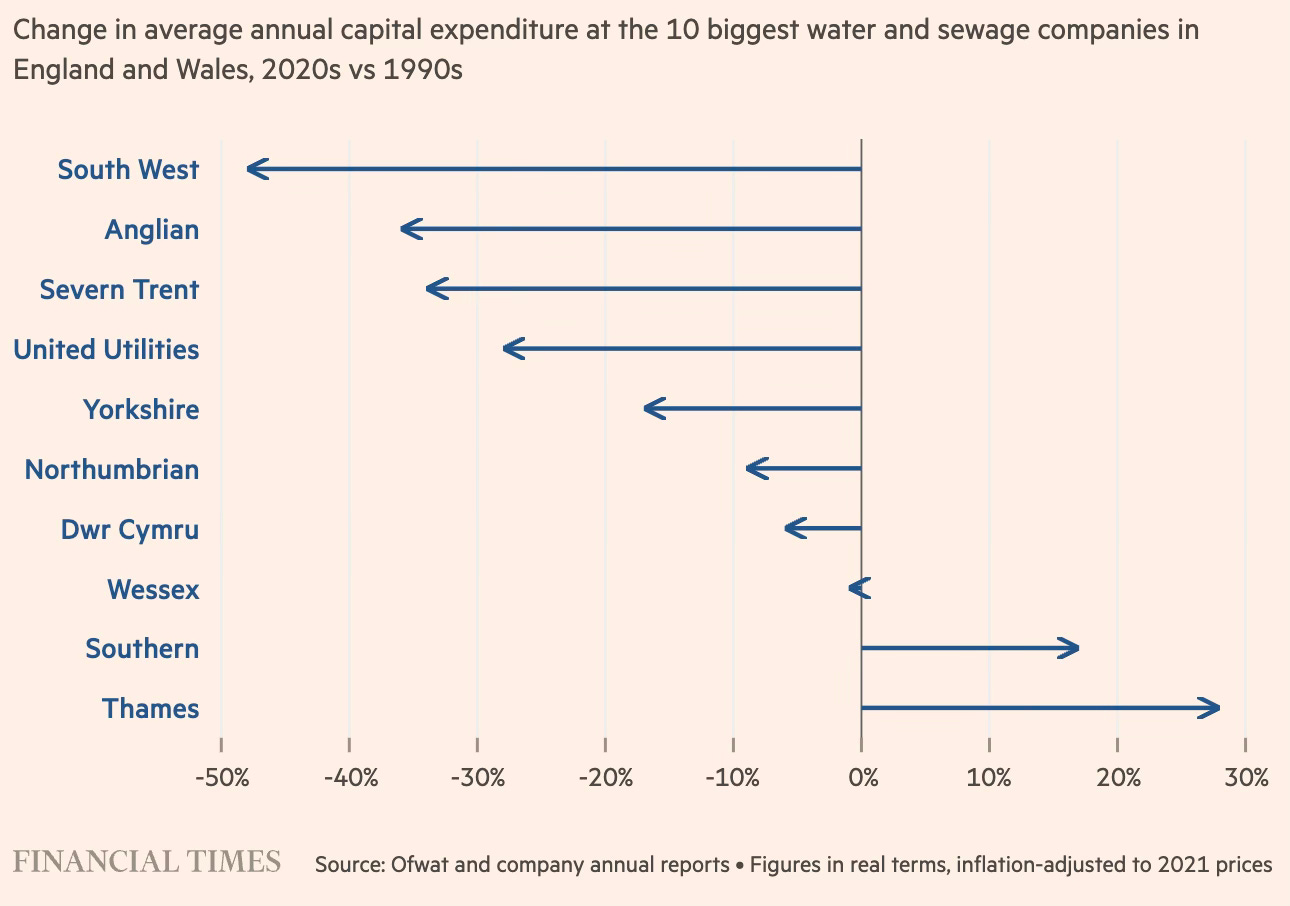

Total spending on waste water infrastructure by the 10 largest companies — excluding Thames Tideway — has failed to rise significantly. Average annual wastewater investment was £295mn in the 1990s, £297mn in the 2010s and £273mn in the 2020s so far.

And this about the worsening quality of waterbodies in the country arising from releases of untreated water.

All 16 companies have been criticised for service failures, including tipping unknown quantities of sewage into waterways, high leakage rates or water outages. The Environment Agency is conducting its largest ever criminal investigation into potential widespread non-compliance by water and sewerage companies at more than 2,200 sewage treatment works, while Ofwat is also running its own investigation into the issue.

This graphic is striking in so far as it shows that all water utilities have cut their investments in wastewater treatment infrastructure since privatisation.

Consider this balance sheet of wastewater and sewage infrastructure

Total spending on important infrastructure, which hit a post-privatisation peak of £5.7bn a year between 1991 and 1999, fell by 15 per cent to £4.8bn between 2020 and 2021, according to a Financial Times analysis of the accounts of the 10 largest providers in England and Wales. The decline was most extreme for wastewater and sewage networks. Investment there has fallen by almost a fifth, from £2.9bn a year in the 1990s to £2.4bn now… The reductions have come despite a 31 per cent real-term increase in water bills since the 1990s — an average of £100 a year per household — and £72bn in dividend payments to parent companies and investors including private equity, sovereign wealth and pension funds in the same period… In 2019, only 16 per cent of England’s rivers and seas met the minimum “good or better” ecological status as defined by the EU’s water framework directive, according to official Environment Agency figures, while about a fifth of the treated water supply is lost in leakage.

The most striking finding from the Greenwich University study on water and sewage privatisation in the UK is this graphic that shows that the “privatised water companies have generated enough cash to cover investment without taking debt”.

Since privatisation, the aggregate cash flow generated by the English and Welsh companies after operating costs was £36bn more than the £123bn they spent on fixed assets such as new pipes and network infrastructure (all in 2017-18 prices), the study found. This suggests their capital spending could all have been funded out of internal resources… On a combined basis, customers today pay about £1.2bn a year — or £53 a year per household — servicing the debt, according to the analysis by Karol Yearwood... Funding capital spending with debt rather than free cash flow enabled the English companies to pay out £56bn in dividends to investors, which include an array of private equity type groups.

In other words, it’s clear that the water companies have assumed such massive debt only to payout large dividends.

And the comparison of the privatised companies with the only public owned utility, Scottish Water, is revealing.

The English water companies have improved efficiencies since they were privatised in 1989. Their revenues have grown by 34 per cent since 1990-91 in constant currency terms, and operating cash flows have increased by 74 per cent over the same period. But the study claims they are not obviously more efficient than Scottish Water, which remains in state hands: its operating spending per household is about 10 per cent lower than the English companies. Customers’ bills in Scotland have fallen slightly in real terms since 2002, when Scottish Water was established, to about £357 per household in 2018. This compares with a 10 per increase in England and Wales over the same period, from an average of £356 per household in 2002 to £395 in 2018.

The study by Yearwood makes extensive comparisons between the privatised utilities and Scottish water on a host of parameters. It’s illuminating and upends the conventional wisdom about private management being superior to public management, at least in developed countries.

All this raises fundamental questions about the desirability of private equity investments in regulated sectors and their regulatory treatment.

“These problems are the failings of a system which encourages companies to extract returns as though it was a high risk business,” said Professor David Hall, a director at Greenwich university. “But water and sewerage services are not high risk.” Other experts have also criticised the regulator. Dieter Helm, a professor of energy policy at Oxford university who focuses on British utilities, said that water privatisation had been a “major regulatory failure”. “The companies were given a £1.5bn green dowry at privatisation and the system was set up to encourage borrowing,” he added. “Were their balance sheets used primarily for capital investment? No. They are private companies so of course they are going to try and maximise profits.” While the practice of companies borrowing to pay dividends is not unknown, it is more controversial in industries — such as water — where the regulator takes financing costs into account when setting prices for services.

The result of all this means that the deeply indebted privatised utilities in UK, and especially Thames Water, are close to renationalisation. In fact, the FT’s Lex column has advocated a “period of temporary public stewardship” would be beneficial and help tackle the complex ownership structure. It may be a good one-time reset to the incentives among financial market participants to wipe out the investors, impose haircuts on creditors, and nationalise the utilities.